SMALL ISLAND STATES PROJECT

Index

Figure 4 Map

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

[ver 3.0 2002/06/04]

Robert Seward

REGIONAL SECURITY IN THE PACIFIC ISLANDS--PART 3

Part 1 Introduction

Part 2 Security Environment

Part 3 The Example of Kiribati, Review and Commentary, Sources

KIRIBATI

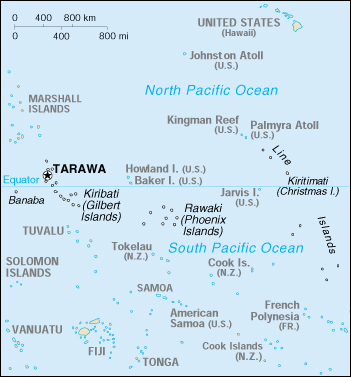

For an idea of the difficulties that Pacific island nations face in policing their territorial waters, consider the predominantly Micronesian state of Kiribati in the central Pacific. Kiribati, which was seized by Japan in 1941, straddles the equator and includes three widely separated island groups—the Gilbert, Line and Phoenix islands—of which only twenty islands are inhabited. (See Figure 4.) The population is somewhere around 85,100 with over 40 percent of the inhabitants under fourteen years of age. The country is small in terms of land area, only 811 square kilometers. On the other hand, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), Kiribati has one of the largest Exclusive Economic Zones in the world, at 3.55 million square kilometers. Of the thirty-three atolls that comprise the country, 40 percent is unoccupied.

Figure 4

CENTRAL PACIFIC OCEAN

Figure 4 shows the extent of the territorial waters of Kiribati, which includes the three island groups—Gilbert, Line, and Phoenix islands—with an EEZ of 3.55 million square kilometers. Source: University of Texas, Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/cia01/kiribati_sm01.jpg.

By agreement, Japanese fishing interests, among others, have entered Kiribati waters as part of a purse-seine joint venture. The Kiribati Maritime Agency has also sought agreements with joint-venture partners to establish a long-line fishing base for the production of fresh tuna for sashimi markets, although inadequate port facilities and air links may work against such efforts.

But for all intents and purposes, much of the Kiribati EEZ, as with most Pacific EEZs, goes unpatrolled. To guard the enormous expanse of sea, Kiribati owns one Australian-built Forum Class small patrol boat called Teanoai. The Teanoai was commissioned in 1994 and displaces 162 tons. The vessel has a top speed of 20 knots and is berthed at Bairiki Island in the Tarawa Atoll, part of the Gilbert Islands.

Intrusions of the EEZ are the rule, not the exception. Kiribati has acted to impound foreign-owned vessels caught fishing illegally, and Palau in early 2002 announced that foreign ships fishing illegally in its waters would face up to US$1 million in fines. In May 2002, the Royal New Zealand Air Force flew reconnaissance over Palauan waters and found nineteen fishing boats, although all nineteen were later found to have licenses to fish there.

According to the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), routine violators of Pacific EEZs include ships from Korea, Taiwan, China, and other distant fishing nations. The FFA—whose members are Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu—engages in monitoring, control, and surveillance measures. As many states lack resources and population, however, enforcement has not been stringent.

Fish piracy is serious. It depletes fish stocks and cuts into the livelihood of Pacific island nations. Because of the outlaw nature of the piracy, illegal boats are frequently armed and dangerous and a threat to legitimate fishers. (See FAO’s Management for Responsible Fisheries Program.) If larger, wealthier nations like the United States and Canada must expend considerable expense and energy in patrolling their waters, imagine the burden tiny Pacific states must bear to police even their inshore waters.

In an example that may serve to demonstrate the difficulties, let alone the cost, involved, Canadian and U.S. aircraft in May–April 1999 detected multiple vessels fishing in northwest Pacific waters in violation of the UN High Seas Driftnet moratorium and the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission protocols. The U.S. Coast Guard cutter Rush set off in chase and, in three separate cases, apprehended Russian vessels, the Lobana-1 and the Tayfun-4, which were then handed over to Russian enforcement. The Rush also seized the Ying Fa, which initially claimed Chinese origin. When China refuted the ship’s registry, the Ying Fa was escorted back to Alaska where it was sold at auction and the crew returned to their homes (China and Taiwan). Scientific analysis of the salmon aboard the Ying Fa confirmed that a significant percentage of the fish were caught in North American waters.

In yet another example, the Australian navy in April 2001 located the South Tommy fishing in waters close to Antarctica under its jurisdiction. After a chase of over 4,000 kilometers and assistance from the South African navy, the Australians boarded the South Tommy off the Cape of Good Hope. The catch was Patagonian toothfish—a very valuable but heavily overfished species. Proving responsibility was less easy: The South Tommy was registered in Togo and had a European captain.

Kiribati may be a typical Pacific island nation. It has no regular military force--certainly no navy. There are police posts on most of the inhabited atolls, and it is the police force that carries out not only law enforcement but also paramilitary responsibilities. (Expenditures for police duty are not available.) Defense assistance, as with most Pacific island states, is provided by the regional powers Australia and New Zealand, including surveillance overflights. Fishing losses to Kiribati are taken seriously, as the country’s economic security depends on fishing income.

Kiribati’s budget for 2002, with the economy in slight decline, estimated total expenditures of around US$42 million. The figure is a decrease of 15 percent over the revised estimates for 2001. Government operating costs, at US$38.34 million, are considered sustainable in the medium term. Total recurrent revenue is estimated at US$30.13 million, with US$15.12 million from fishing licences and US$8.1 million from import duties, the principal income sources. The budget will be balanced largely by a drawdown from the Revenue Equalisation Reserve Fund (RERF) of US$9 million. As the figures indicate, fishing accounts for around 36 percent of revenue.

The economy of Kiribati is tiny and has been subject to wide fluctuations in recent years. Foreign aid, to give some indication of the magnitude of economic ills, has oscillated between 20 percent to 50 percent of GDP. The primary donors are Japan and Australia. (In 2000, Japan provided $US 9.9 million in grant and loan aid.) Another sizable source of income is remittances from workers abroad—over $5 million yearly—some of it the result of 225 Kiribati men working on foreign pole-line, long-line, and purse-seine vessels, including Japanese vessels. Only a little over 20 percent of the population holds formal employment.

Kiribati is also playing the Pacific passport game. According to official figures, twenty-five Kiribati Investor Passports (so-called “Green Passports”) were sold in 2001, at a cost of US$15,000 each. In addition, 343 Kiribati Residential Permits were sold, at a cost of US$3,500 each. Most permits are sold to Chinese or Taiwanese passport holders. Together, these sales generated more than US$1.35 million for the Kiribati government.

Other than the sea, the country has few natural resources. Phosphate deposits were exhausted by the time of independence in 1979. Efforts are being made to diversify the economy, primarily through fishery projects and tourism, but visitor arrivals are to date a mere trickle. The creation of the 200-mile exclusive economic and fisheries zone has provided some hope of developing marine resources to a point where fish could be the country’s main source of revenue through export earnings and licensing fees paid by fishing nations such as Japan. (There are large stocks of tuna in Kiribati territorial waters.) Unfortunately, in such a vast area, there are few good anchorages and only four main ports of any size—Banaba, Betio, English Harbor, and Kanton.

Fishing is by no means an economic issue alone. As documented by an article in the Pacific Daily News in May 2002, “Illegal Entry into Guam Foiled: Men Caught after Swim to Shore from Taiwan Fishing Boat,” illegal vessels often offload illegal immigrants. In April 2001, eight Chinese men were found swimming to shore, after having hijacked a Taiwanese fishing vessel and shackling the officers and crew. News reports indicate additional attempts at illegal entry in the same year. In two separate incidents in April 1999, Taiwan fishing boats heading for Guam, a U.S. commonwealth, were intercepted carrying a total of 257 illegal immigrants. Reports of attempts at illegal entry have become commonplace.

A clear picture of illegal immigration across the Pacific will never be known, but it is clear that, where it is successful, illegal immigration can be a burden to local communities and taxpayers in terms of social services and lost job opportunities. The burden is greater on countries with limited ability to respond in a humanitarian fashion to prevent the loss of life at sea. If the interdictions by U.S. authorities are an indication, many of the migrant vessels are dangerously overloaded, unseaworthy, or otherwise unsafe.

Coastal protection is increasingly breached. As for the United States, even it has not had unlimited resources to deal with illegal immigration. Only two Coast Guard cutters patrol the waters around Guam, although for Guam and the Northern Marianas Islands as well, air surveillance is employed. This vigilance appears to have succeeded in slightly lowering the number of illegal immigrants attempting to enter these U.S. territories. In 2000, in all U.S. waters where the Coast Guard patrols, there were 4,210 interdictions at sea. The figure was down somewhat in 2001, but by April 2002, U.S. authorities had already detained 2,995 undocumented migrants at sea. Among Pacific island interdictions, the largest number of illegal migrants is from China. While maritime migration continues, recent interdictions are fewer in part because smugglers have changed their routes and their tactics. Guam seems to be a favored landing spot. From the Asia Pacific, illegal migrants have also come from Japan, Korea, Philippines and Taiwan.

To be sure, around the Pacific, resources dedicated to near-shore patrols are few for illegal entry and even fewer for open-water patrols. Given its remoteness, Kiribati is unlikely to have much worry about illegal immigration, and one might cynically suggest the sale of its passports. Elsewhere in the Pacific, the issue is of concern. But Kiribati does understand illegal fishing in its territorial waters. Kiribati relies heavily on license fees from distant fishing nations; its economy is supplemented by income from exports of seaweed, live fish, and other marine products as well as remittances from Kiribati citizens employed abroad, mainly as seamen. In total, as indicated above, fishing contributes to over one-third the country’s revenue. The island nation faces significant constraints common to most island atoll economies: small land area, limited population, physical remoteness, geographical fragmentation, a harsh natural environment with infertile soil, and limited exploitable resources. So it must protect what it does have.

REVIEW AND COMMENTARY

The development of a military capability is probably beyond the means of most Pacific island nations, should they even contemplate such a move. Fiji maintains a sizable force primarily by sending almost one-third of their armed forces abroad on peacekeeping missions. Because of economic conditions, Papua New Guinea, a country of considerably larger size, has difficulty maintaining a force of equivalent size. For the most part, the Pacific island states maintain security by use of police organizations.

While states in the region are generally weak and ill-prepared for non-traditional security threats, the situation is not totally bleak. The prospect of interstate conflict in the Pacific is low. Few countries have strong armed forces—even those that have a standing army. The close alliances countries have with the United States, New Zealand, and Australia, on the other hand, provide a modicum of safety for the region. A direct military attack on Pacific island states would, in any event, seem unlikely.

Nevertheless, no matter how broad or how narrow one defines security, many security matters are outside the hands of Pacific island states. Significant issues for the security of the region lie in the nature of the relationships among the region’s major powers—China, Japan, India, Russia, and the United States—and the regional powers Australia and New Zealand. In relation to these larger countries, Pacific states themselves have little power. Japan’s refusal, for example, to negotiate regionwide collective fishing agreements is a case in point. There is little Pacific countries can do. Various unilateral moves by the George W. Bush administration also indicate the relative powerlessness of smaller states.

The region is not, however, without some influence as China’s recent courting of island states demonstrates. Yuan-diplomacy is at work throughout the region and sometimes irrespective of diplomatic recognition; Papua New Guinea receives ODA despite its recognition of the Taiwan government. Small though they may be, Pacific island states have votes in international forums, and they are wooed accordingly.

As noted above, there are a variety of regional bodies organized not only for regional cooperation but for international representation of regionwide views as well. These do serve to strengthen the region, even as political initiative is wanting.

Rather than external threats, the challenges to the internal stability and cohesion of Pacific countries are of greater importance. Worsening economies place pressure on social structure, particularly where public expectations are unrealistic. Economic disparity continues to create strains and distributive conflict even where economic performance improves. The unrecognized security issues involving ethnic conflict, land rights, and widening gaps between the privileged and underprivileged need seriously to be addressed.

Regional governments have a responsibility to ensure, whether by police or armed forces, that there are sufficient resources to protect citizens whatever the security threat. Budgets are stretched thin in many countries; nevertheless, both Fiji and Papua New Guinea expend about one percent of GDP on defense. Compare this with Australia where defense represents 1.9 per cent of gross domestic product. Given the economic climate, it is unreasonable to expect that regional governments will appropriate additional sums, even where scenarios suggest high risk.

Health and the environment are also high on the list of security issues. In health, the SPC, WHO, UNFPA, and many NGOs are working on AIDS and other health problems. Considerable strides have been made in awareness programs, in providing resources and action.

These Pacific countries also face security threats from smuggling, false documentation, and crime, including international financial schemes. International terrorism is now added to this list. While these are typically police matters, interregional security cooperation is all the more vital because of the smallness of the countries, their geographical spread, and the modest nature of most police forces. Fortunately, several regional organizations—SPCPC, OCO, PIDC, RHPM, PILOM—exist to share information and to train personnel.

In the Pacific where there are few standing military forces, the concepts of what constitutes security and who is responsible are blurred. Here, security does not conveniently fit typical academic definitions. If security, for example, involves prevention and deterrence, then, given the realities of Pacific life, the mandate of police and military forces needs expansion. Training in mediation and conflict resolution become appropriate. The peacekeeping role of such forces should be kept in mind. Scholars with a peace orientation may object, but in these small, weak, but complex developing states, the military and police are part of the development context and their work has links to the economic, social, and community development of the nations.

SOURCES CONSULTED

Ambrose, David, A Coup that Failed?: Recent Political Events in Vanuatu (Canberra: National Centre for Development Studies, Australian National University, 1996).

Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Bank Outlook 2002 (Manila: ADB, 2002).

Australia, AusAid, Pacific Program Files 2000-2001, Basic Indicators, http://www.ausaid.gov.au/publications/pdf/pacprofiles2000_01.pdf.

BBC News, “Papua New Guinea Soldiers Mutiny,” http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/asia-pacific/newsid_1866000/1866204.stm, 2002/03/11.

Crocombe, Ron, “Enhancing Pacific Security,” Report for the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2000/06.

Fiji Government Website, http://www.fiji.gov.fj/fijifacts/fijitoday2000.pdf .

Fish Information Services, http://fis.com/fis/.

Forum Fisheries Agency, http://www.ffa.int/.

Georges, P. T. Vulnerability: Small States in the Global Society (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 1985).

Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufmann, The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, http://www.iattc.org/.

Japan International Food and Aquaculture Society (JIFAS), www.jifas.com.

Japan, Japan International Cooperation Agency, http://www.jica.go.jp/.

Japan, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, http://www.maff.go.jp/eindex.html.

Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Oceania ODA,” http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/summary/1999/ap_oc01.html.

Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/area/kiribati/data.html.

Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius Tara, “A Weak State and the Solomon Islands Peace Process,” Pacific Islands Development Series, East-West Center, 2002.

Lal, Victor, Fiji: Coups in Paradise: Race, Politics and Military Intervention (London: Zed Press, 1990).

May, Ronald, “Papua New Guinea: The Security Environment,” in Charles Morrison, ed., Asia-Pacific Security Outlook 2002 (Honolulu: East-West Center, 2002).

OECD, “Aid Charts—Recipient Countries and Territories,” http://www1.oecd.org/dac/images/AidRecipient/kir.gif.

Ogashiwa, Yoko, “The Pacific Islands Countries in Asia-Pacific Regional Frameworks,” Hiroshima Peace Science, 20:327-49 (1997).

Pacific Islands Report, “Pacific No Longer Safe, Stresses Forum Secretary General Levi,” 2002/03/10.

Papua New Guinea, Department of Defense, http://www.defence.gov.pg/.

South Pacific Commission, http://www.spc.org.nc/.

United Nations, Oceans and Law of the Sea, Division for Ocean Affairs and Law of the Sea, http://www.un.org/Depts/los/index.htm.

United States, Coast Guard, http://www.uscg.mil/hq/.

United States, Library of Congress, Country Studies, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cshome.html.

Ward, Alan. “The Crisis of our Times: Ethnic Resurgence and the Liberal Ideal,” Journal of Pacific History, 27(1):83-95 (1992).