Searching for the atmosphere of Baudelaire’s 19th century Paris: Enthusiastically pursuing research to bring its buried history to light

French poet Charles Baudelaire is famous for such works as the poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil). Professor Toru Hatakeyama, whose research focuses on Baudelaire, speaks passionately about the “provocative and defiant power” of the language he used in his poetry. In an attempt to read Baudelaire’s literature through the eyes of Parisians living 200 years ago, Professor Hatakeyama tirelessly and patiently unearths literature that has been buried by the tide of history. The professor enthusiastically teaches his students the power of language and a healthy skepticism in his classes on French language and literature, and rhetoric, always cherishing the precept that “literature is the study of the zest for living.”

Toru hatakeyama

Professor, Department of French Literature, Faculty of Letters

He obtained his master’s degree from the Division of European and North American Studies at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology. After completing a doctoral program at Paris-Sorbonne University, he was awarded a Ph.D. Professor Hatakeyama’s areas of specialism are French modern poetry (Baudelaire), French education history, and Baudelaire’s reception in Japan. He served as an associate professor in Nihon University’s College of Law before joining Meiji Gakuin University as an associate professor in the Faculty of Letters’ Department of French Literature. Professor Hatakeyama took up his current position in April 2020. His recent books include Enjoying French Literature: From Virgil to Le Clézio (co-author, Minerva Shobo, 2021).

-

Both classical and modern. The diverse faces of Baudelaire

My research primarily studies the poetry of 19th century French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire.

As well as being the author of provocative poems defying the bourgeois morality of the times, Baudelaire was a poet who advocated a new form of beauty for the age, rather than clinging to the aesthetic norms of the past. For my doctoral dissertation, I investigated the secondary education that Baudelaire received, and today I use my findings from that research to study such matters as how Baudelaire composed his poems, the relationship between poetry and painting, and the way in which Baudelaire incorporated the techniques of expression used in classical education into his own poetry. I am also interested in Baudelaire’s reception in Japan. In particular, focusing on the poet Ote Takuji, who translated some of Baudelaire’s poems into Japanese from the original text in the late Meiji and Taisho periods, I am studying Japanese modern poetry through the relationship between Ote and Baudelaire.

Baudelaire is a highly multifaceted poet. While he has a classical side, it would also be fair to describe him as a modern poet. He was an eccentric, an intellectual, and a man who dearly loved his mother. Personally, my strongest feeling about this man of diverse faces is that he was someone with a tremendous facility for language, whose poems in particular have a provocative and defiant power. This is something I felt the very first time I encountered one of Baudelaire’s poems.

I was a high school student when I began reading Baudelaire. At that time, I hated everything, and looking back now, I think I was in the grip of an intensely rebellious phase. I had a very powerful sense that I could see the world only through the prism of my family’s standards and societal norms, and was not looking at the world through my own eyes. I was desperate to leave home and take off the “glasses” of other people’s norms. It was just then that I happened upon Baudelaire’s prose poem Anywhere Out of the World. And so it was with this fervent wish in mind that I resolved to escape from Japan by going to study in the U.S. for a year.

At the time, I probably had the rather narcissistic idea that I was cool because I read Baudelaire, who was little-known to those around me. In fact, I did not really understand the meaning of his poems all that well. But what is certain is that, above all else, I felt the energy of Baudelaire’s defiance and provocativeness emanating from his words, and I was attracted to that power. I still feel the same way today.

Considering Baudelaire’s poems through the lens of the education he received

It is not all that simple for Japanese readers in the 21st century to see Baudelaire’s works through the same eyes as 19th century French people. The meanings of words have changed between then and now, as has the education received by readers. Some of the people and events tacitly alluded to in his works are no longer common knowledge. It would be wonderful if we could travel back in time to those days, but as we cannot, I am pursuing my research as though trying to read his works using a special telescope enabling us to peer back in time and replicate the past.

When I was at graduate school, I undertook research focused on the education Baudelaire received, to provide a basis for understanding his literature. This was because I thought a knowledge of the content of school education in those days would lead me to an understanding of Baudelaire’s cultural foundations. However, the 19th century secondary education that I wanted to learn about was an area regarded with a kind of hostility within the broader field of French literary history formed after the establishment of France’s Third Republic. This is because the secondary education received by Baudelaire focused on classical knowledge based primarily on Latin literature, but this kind of classical education was rejected as outdated following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. As a result, when I began my studies at a French graduate school, the relevant literature and materials had been buried by the tide of history and I was only able to find them in piecemeal fashion. I just referred to my research as being like peering through a telescope, but the reality is that, when I started out, the lens of that telescope had been shattered and its pieces scattered far and wide. In an effort to repair this lens, I have spent a great deal of time searching for and gathering together textbooks and reports from those days. On rare occasions, as I search through this immense collection of materials, things come into focus and I am able to see something that was previously not visible to me. There really is no substitute for the joy I feel in those moments.

My most recent exciting lightbulb moment when everything came sharply into focus was the realization that the classical theme of the Triumph of Bacchus, which has been depicted in paintings by such artists as Carracci and Poussin, is also woven into Baudelaire’s poems. “Wow! I can see it so clearly!” When I realized that, it felt great and I was incredibly happy. But an instant later, I thought, “Hang on a minute.” It occurred to me that someone might already have discussed this point, so I began to go back through past studies and commentaries, but for all my searching, I could not find any reference to it. Strangely, in that situation, anxiety wins out over the joy of having made a discovery. It might be something perfectly commonplace that everyone already knows. In the words of a friend of mine, it is as though you thought you’d taken a narrow path that nobody else knows about, only to suddenly find it leads onto a busy street. Panic-stricken, I checked until I could check no more and finally gave my presentation at an international conference, where my former lecturer from my time studying in Paris was kind enough to praise my argument as convincing. I was relieved and happy to hear his feedback.

A healthy skepticism is important in both research and education

When I think I have “discovered” something in research, I feel tremendous joy and excitement in that moment, but then I become highly skeptical and battle with the thoughts that I might be wrong and that Baudelaire might not have thought that way. Losing this skepticism might disqualify me from being a researcher. From time to time, I tell my students about the importance of maintaining a healthy skepticism.

Even when I comment on my students’ views, I preface my words with the disclaimer, “Just because I’m your lecturer, it doesn’t mean my opinion is unassailably correct.” There are diverse opinions about everything, with reasons and backgrounds to each person’s view. This applies to both the interpretation of literature and approaches to social phenomena. I present a variety of views in my classes, but I avoid suggesting which is correct. I leave it up to the students themselves to think about which opinion they agree with. I believe the role of university education is to cultivate the ability to think for themselves when asked such questions.

Blindly believing that something is categorically correct is a terrible thing. The philosopher Michel de Montaigne, who lived through the French Wars of Religion in the 16th century, ended up reaching a skeptical position with his motto “Que sais-je?” (What do I know?) Furthermore, in his book Essais, Montaigne wrote, “I am a little tenderly distrustful of things that I wish.” Whereas it feels good to find an opinion that accords with one’s own, having one’s ideas rejected or questioned is uncomfortable. However, there is nothing worse than coming into contact only with the information that you seek or that fits your own way of thinking and blindly believing it. Precisely because diversity is such a key social issue right now, I teach my students—with a note of self-reproof—about the importance of maintaining an awareness that nothing is categorically right and that you might be wrong.

The “Hatakeyama dojo” providing a thorough training in rhetoric

The two key features of my seminar classes is that students take the lead in running them and that there is a thorough focus on rhetoric. Rhetoric is often misunderstood to be glib, frivolous wordplay, but it is actually the art of expressing one’s thoughts logically to convince others.

There are five elements to rhetoric: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery. You invent what you ought to say, decide on the arrangement of the order in which you will say it, think of the style in terms of the actual words and metaphors you will use, commit it to memory so you can look the audience in the eye while you speak, and pay attention to the speed at which you speak and your body language in the delivery. I have my students put these five tenets into practice in their seminar presentations.

Compulsory for all students in the Department of French Literature, the graduation thesis provides an opportunity to fully mobilize the rhetorical techniques mastered through seminars, along with the French language skills and knowledge of French literature and Francophone cultures that students have been building up and deepening since their first year. As I am very demanding not only about content and rhetoric, but also spelling and grammatical errors, my seminars have come to be referred to as the “Hatakeyama dojo”<laughs>. Students moan about writing their graduation theses, but the lecturers who mark and correct them also put in a lot of work. However, the lecturers in the Department of French Literature are all united in the view that it is worth the effort, no matter hard it might be. Students and lecturers together work through their thesis in earnest, so we are really pleased when something good emerges, and find it deeply moving when we perceive those four years of study bearing fruit.

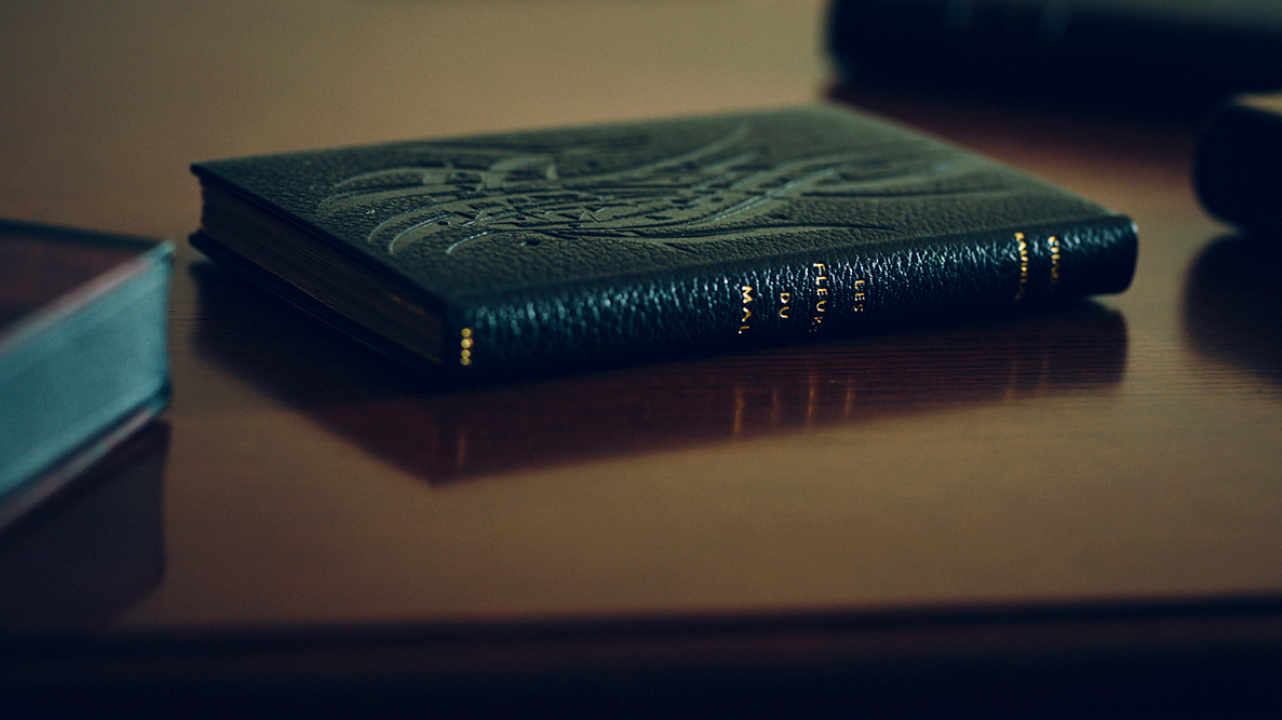

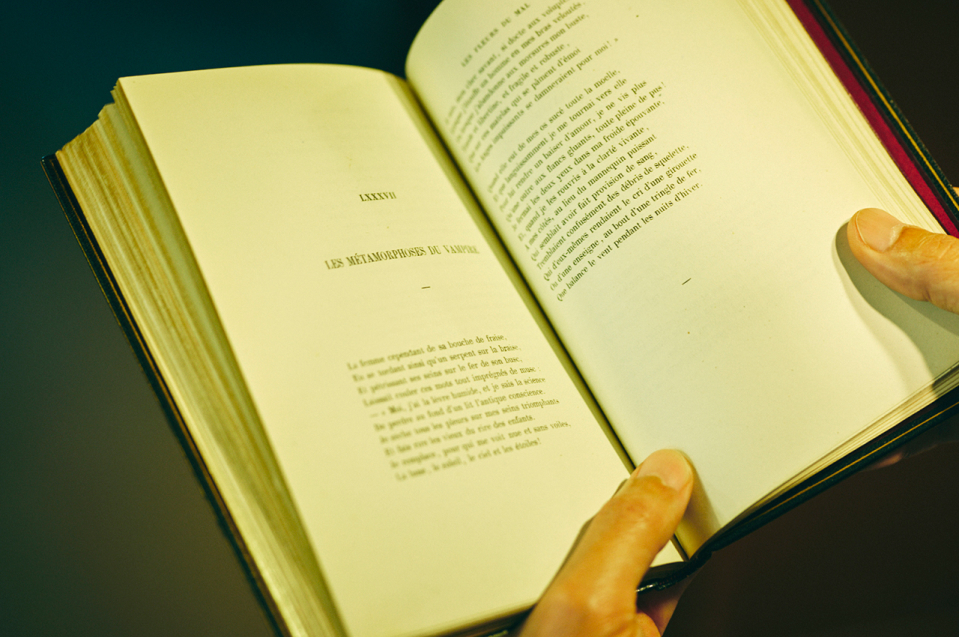

The significance of Meiji Gakuin University’s first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal

This year, many books of great value for the study of French literature have been added to Meiji Gakuin University’s collection. Of these, Baudelaire’s debut Salon of 1845, Les paves (The Wreckage)—published a year before his death—and an 1857 first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal are particularly worthy of attention. This first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal is very precious, as only 1,300 copies were printed at the time and it contains six poems subsequently ordered to be deleted following a prosecution. Also added to the collection were the 1855 publication Revue des Deux Mondes (Review of Two Worlds), Baudelaire’s translations of Edgar Allan Poe, Les Paradis artificiels (Artificial Paradises), and Baudelaire’s writings on Wagner. Added to the second and third editions of Les Fleurs du Mal already in our library, this means that Meiji Gakuin University may well be the only Japanese university with such an extensive collection of rare books associated with Baudelaire. Several years ago, I participated in an international conference held at the Bandy Center for Baudelaire Studies at Vanderbilt University in the U.S. The center had a huge Baudelaire collection encompassing his complete works from around the world, covering everything from a first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal to Japanese translations. I was overwhelmed by how extensive the center’s collection was and it was my desire to create an environment that resembled it—however remotely—at Meiji Gakuin University that led to our recent purchase of the first edition.

The fact that I am a researcher specializing in Baudelaire is not due solely to my own efforts. I am where I am today thanks to the research built up by many professors over the years. For example, I would not have been able to conduct the kind of research I do now without the complete works of Baudelaire translated by the late Yoshio Abe (Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo). Upholding and passing on this unbroken legacy is a great responsibility as a researcher and I regard the fact that I have been able to bequeath a valuable collection of Baudelaire’s work to Meiji Gakuin University as one form of that legacy.

Besides me, Meiji Gakuin University’s Department of French Literature has many other lecturers who dedicate themselves to both research and education. The links between Baudelaire researchers down the centuries and my ties to my fellow lecturers in the Department of French Literature today bore fruit in the purchase of this first edition. Naturally, one must pass on to the future not only objects, but also the people who use them for research. At the risk of sounding self-important, I want to contribute to bequeathing both objects and people to the university, in order to create an environment in which we can confidently say to people, “If you want to research Baudelaire, come to Meiji Gakuin University!”

“What use is literature?”

I am often asked what the point of studying literature is and how it helps people. One answer is that people develop the ability to use words carefully. Students who have had the experience of diligently writing a thesis using the knowledge and rhetorical skills they have spent four years learning will understand how important the usage of words is, as one has to think deeply about the background and meaning of every single word one uses in that thesis. I think it would be wonderful if, when asked after graduation what they learned in the Faculty of Letters, my students felt they could reply that they learned to value words.

Aside from that, I think we will find the key to the answer if we think about the question “What use is literature?” from the perspective of the question “What is literature in the first place?”

Today, most of the old literature we have relates to myths, legends, and religion. Among them are, for example, the Bible, the Quran, the Kojiki, the Aeneid, and the Divine Comedy. What all these texts have in common is that they attempt to answer the questions “How was the world created?” and “Why am I alive here and now, and how should I live in the future?” In other words, literature has continued to be written in pursuit of an answer to the question “Why am I alive?” In the words of my old lecturer, “Literature is the study of the zest for living.” When people ask what the point of studying literature is, I want to ask them in return, “Don’t you think there’s a point in asking why we’re alive?”