What is a return to creative roots that goes beyond “identity” to grow a brand?

We are surrounded by a broad range of brands, from luxury products to those that are more reasonably available. Creating a brand identity is an important part of establishing a brand, but becoming overly concerned with “identity” as consumers perceive it can lead to the brand’s decline. Associate Professor Mitsutoshi Otake conducts research on how companies suffering from “the curse of identity” can renew and rebuild their brands, focusing on points of contact with markets and consumers.

Mitsutoshi Otake

Associate ProfessorDepartment of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics

Ph.D. (Business), Hitotsubashi University Business School. In 2012 he became a full-time lecturer in the Meiji Gakuin University Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics, and he took his current position in April 2015. His research focus is consumer culture theory and market strategy theory. His main research themes are formation processes in consumer culture, market perceptions, and organizational inertia, and he engages in research on brand management from the perspectives of legitimacy and organizational inertia. His hobbies include reading the histories of various companies and thinking up new styles of corporate history.

-

Market strategy theory: The business administration domain that is closest to consumers

The field of business administration contains many research areas, including accounting, finance, organization theory, and management strategy. Among those, my specialty is market strategy theory, also called marketing theory. Market strategy theory is a research area that attempts to understand marketing as a series of processes called the “Four Ps,” namely, Product (products and services that meet the needs of the market), Promotion (how consumers are notified of a product’s existence), Price (pricing suited to the provided value), and Place (where products are sold). Adapting these activities to markets is a fundamental and important theme in marketing.

Key to the theory of market strategy is the idea of “product/market fit.” Products can be made fit at various levels, the most obvious way being to investigate consumer needs and create something that meets those needs. But there are also products that realize a more “high-level” fit in that they satisfy a latent demand that even consumers did not know existed, a prime example being the Sony Walkman. How to create such a higher-order fit that makes consumers aware of new needs, rather than merely meeting already manifest needs, is another important theme in market strategy theory.

Market strategy theory is the business administration domain that is closest to markets, that is, to consumers. Many scholars thus study both marketing theory and consumer behavior theory. I am one such researcher, interested in the processes by which consumers perceive the “genuineness” (legitimacy) of a brand within consumer behavior theory. Namely, I conduct research from the perspective that people may use past experiences to develop an image of which brands suit them, and that they judge authenticity in relation to that image.

The “curse of identity” stands in the way of taking on new challenges

When I talk to business leaders, they often say things like, “We want to restyle our brand, but we can’t seem to get started.” Such restyling of a brand is called “rebranding,” and it provides an excellent example of “easier said than done.” Many companies fail to rebrand despite market changes demanding that they do so, making them seem behind the times.

One factor that prevents restyling is market expectations. The essence of brand management is pursuit of identity, but if the company remains overly conscious of brand image in the marketplace, that image restricts the company’s activities and proposals, preventing it from taking on new challenges. Marketing research also considers the concept of “marketing myopia,” which refers to the fact that if a company too narrowly defines what its business is, it will lose out to other companies. Another source of concern, particularly for large brands and long-established companies, is the phenomenon of “organizational inertia,” in which the company’s self-definition and identity becomes so prevalent as to make change impossible.

Rebranding Nishikawa Co., Ltd.

My current research focuses on how we can break through such organizational inertia and brand rigidity.

Since they occur external to the company, responding to market changes seemingly requires “outward” activities, but that is not always the case. The more a company looks toward the market, the more it is placed side-by-side with other companies, so even if it can change, such change too will occur side-by-side with those companies. If that is the case, I believe, rebranding will be more successful if the company instead takes an “inward” look, back toward the origins of the brand.

So what specifically does it mean to consider a brand’s origin with the aim of breaking through the brand’s rigidity? Allow me to explain using the example of Nishikawa Co., Ltd., a manufacturer of bedding products.

Nishikawa was founded over 450 years ago, during Japan’s Warring States period, and was primarily known as a manufacturer of futons. Today, one of the company’s signature products is “AiR,” a series of highly functional mattresses launched in 2009. This series became a big hit across a wide range of buyers because of its innovative and colorful designs and the company’s use of top athletes in advertising.

The current president initially proposed the development of AiR, but the idea was fiercely opposed within the company before it was brought to market. The main reason for this opposition was that it “didn’t fit Nishikawa.” The company primarily marketed to older customers, so all their products had subdued colors. Some in the company worried that releasing a product in such garish colors would tarnish the brand image they had worked so long to build.

The president, however, knew some surprising aspects of Nishikawa’s history. During the Edo period (1603–1868), the company had realized a hit product by colorfully dyeing mosquito netting, which had always been sold in neutral colors. The president was thus able to convince the others, saying that while the company had once been innovative, lately they had not been, and that they should release a product that would evoke surprise in the market.

[Source: Otake, M. (2017). “Reinforcing and mitigating inertia related to brand management: Reconstructing what brands should be by creatively returning to their origins.” Marketing Journal 146, 96–111.]

A brand’s origin can revitalize it

Reflecting on the past, we should consider when the company was founded or when its brand took off as a starting point. But rather than simply returning to the past, we should “creatively” return to that origin by reinterpreting it in a modern way. Doing so provides a source of power for breaking through brand rigidity. In the case of Nishikawa, this means reflecting on how the company had a big hit by dyeing mosquito netting, but also not simply repeating that effort, but instead reinterpreting that previous success. Just as they had added color as a way of creating appeal for the high performance of their netting, they could add color to emphasize the unevenness, and thus the high performance, of their mattresses, thereby successfully revitalizing their brand. Such a creative return to brand origins does not involve listening to the market at all, but even so, it is a way to express the brand’s identity and significance, which I think provides the potential to create something different from other companies.

Providing high-value products and services by paying close attention to the ideals and background of the brand’s founder sounds like a natural thing to do, but when making observations in the field, I notice that many companies are so concerned with what the market tells them at the time that they lose sight of their own essence. Reflecting on origins is a very important part of creating a brand that stands out yet fits a changing market.

Aiming to bridge business and academia

I got my start in marketing research as a student, having become interested in it while participating in promotional activities at the company where I interned. To learn more, I read papers and books by Hiroyuki Itami, who is internationally highly accomplished in the field of management strategy theory, as well as the marketing theorist Junzo Ishii, and the consumption researcher Takeshi Matsui. I still remember how impressed I was when I realized that by knowing a little theory, I could more deeply understand the world.

Dr. Itami in particular conducts research that is highly proximal to actual corporate practice, serving as an outside director for many companies. Influenced by that, I hope to become a researcher who can bridge gaps between business and academia. To that end, I hold study sessions and workshops with practitioners to expose them to the latest case studies and create opportunities to present findings from my research, and my research on returning to creative origins originates from realizations I make through dialogue with people from various companies.

Seminars for learning about marketing in the field and in practice

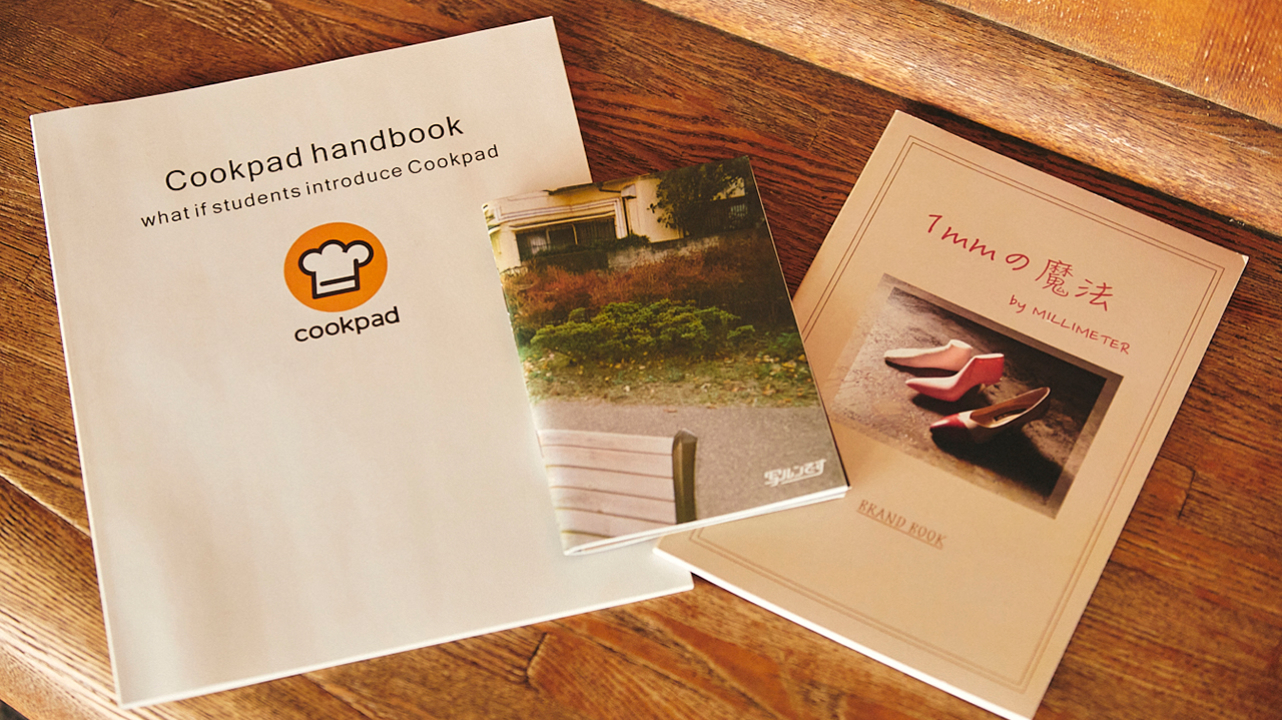

In the education of my students, I emphasize their engagement with the field. In my seminars, students encounter practitioners involved in branding and other marketing activities, working to plan and execute projects that somehow contribute to society. Our previous activities include events that let high school students experience the fun of marketing, and directly interviewing people involved in brand management to produce a “brand book” that conveys the essence of a brand through photos and text.

It is very meaningful for students wanting to someday work in marketing to gain experience in the field and discover their shortcomings. In addition, seminar activities allow students to learn about marketing through practice. In the case of the brand book, students could not only learn about companies and brands through interviews, they could also use the contents of the brand book to experience engaging in their own marketing. These experiences make students more interested in academics and more motivated to write their thesis. During these activities, some students also find internships that lead to employment after graduation. Perhaps one advantage of taking business administration as an academic discipline is that students can so closely connect their studies with their future career.

In the future, I hope to write papers with seminar students who are interested in my research theme as coauthors. I hope those students will eventually become fellow researchers, and that we can conduct research while teaching each other.

My starting point was my carpenter father

Sharing my research in this way has made me think about what my own “origin” was. Looking back, I think it was my father.

Since the time I was born, my father ran a small woodworking factory that made furniture. It was a typical small factory, most of its work being furniture and fittings for libraries or subcontracting work for major manufacturers. When I was a child, I used to wonder why the furniture he made went out into the world without the name “Otake” branded on it, despite the hard work he put into making it. So far as I was concerned the products he made were his company’s, but all the buyers knew was that they were purchased from some bigger company. Thinking about that made me feel sorry for my father, a complicated emotion not unlike sadness. That’s how I felt, at least; my father apparently didn’t feel the same way.

However, that feeling of discontent may be what led to my interest in market strategy theory and branding among the many areas of research in business administration. Well, today I can look at things so simply, but perhaps I have a selective memory, and am putting a bit of a positive spin on things. I suppose that too would be a form of “creatively returning to one’s origins.”

How will the COVID-19 pandemic change marketing research?

Against the backdrop of economic instability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, sharing services have spread throughout society, allowing people to share things with others, from cars to daily necessities, or to borrow them only when needed. This acceleration toward sharing is affecting marketing research in various ways, because much of marketing theory and consumer behavior theory is the study of understanding purchase decision processes based on the premise of buying things.

My own research newly considers the source of real identity as possibly different when we look at things from the premise of buying them versus borrowing or sharing them. Perhaps when viewing a 1,000,000 watch, our opinions regarding whether it is a fit for us varies according to whether we think of it as something to purchase, something to borrow, or something to buy and later resell online for 700,000 after we’ve become bored of it. This may make it difficult to apply to sharing economy conventional models of decision-making processes for purchasing.

The expansion of sharing and other remarkable changes in society are opportunities for finding new research topics and stimulating our motivation as researchers. As the world around us changes, so too does our research perspective. I hope to continue working on finding research topics so that I can help practitioners gain new perspectives, and be of use through my articles and books.