Peace does not mean compromising and shutting up; it begins with nonviolent transformation of conflict for mutual benefit

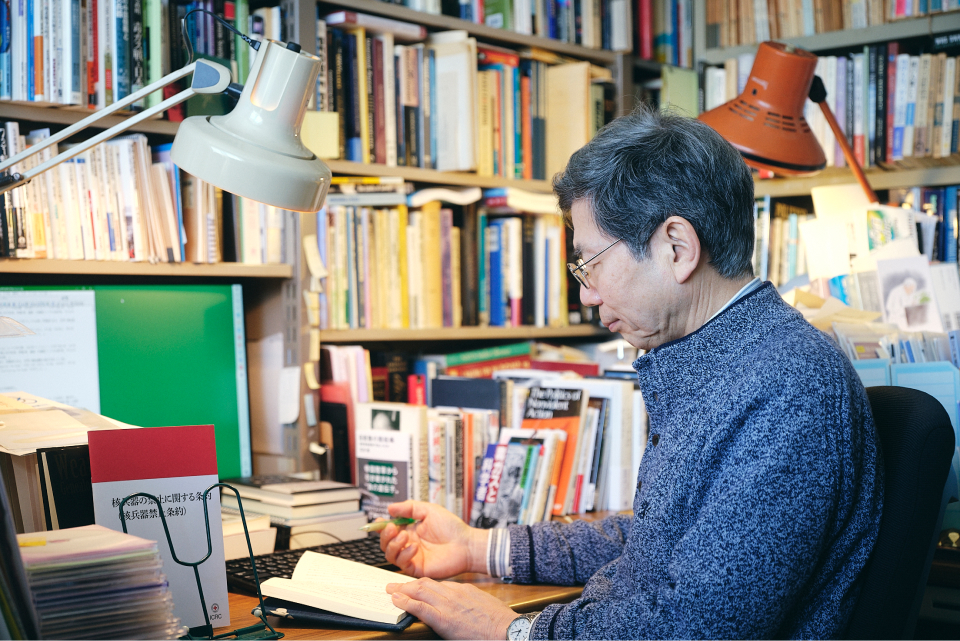

Takao Takahara

Professor, Department of International Studies, Faculty of International Studies

Graduated from the Faculty of Law (Politics Course) and the Faculty of Law (Public Law Course) at the University of Tokyo in 1978 and 1979, respectively. After taking positions as an assistant professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Tokyo and in the Faculty of Law at Rikkyo University, he joined Meiji Gakuin University in 1985 to become one of the founding members of the Faculty of International Studies. He specializes in the fields of international politics and peace research, and has been director of the University’s International Peace Research Institute since 2014. He is on the international advisory board of the Peace History Society, is former international council member of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, and currently serves as council member for the Peace Studies Association of Japan, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Peace Association, and the NPO Peace Depot.

-

What are peace studies? And what is peace?

When you hear the word “peace,” what comes to your mind? A world without war? Sure, that’s important. Peace is an important human value, and peace research aims at promoting the value of peace. Students in my seminar study under the theme “international relations in postwar Japan.” Since Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, “peace” to the Japanese has meant, above all else, no more war. Japan’s constitution, which stipulates that the country renounces war altogether, is known by the name “Peace Constitution.”

The postwar world, however, saw an unprecedented arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, posing a continued threat of eradicating humankind in a nuclear war. It was a situation not unlike two men pointing guns at each other, fingers on the trigger, while standing in an arsenal with gunpowder stacked to the ceiling.

Preventing nuclear war was therefore of utmost concern to postwar international society. This was the awareness under which the International Peace Research Association was established in 1965. Yet despite the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the end of the Cold War, the nuclear peril continues even today. This is the concern behind the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which recently came into effect.

Since around 1970, however, the concept of “peace” has changed, because peace researchers noticed that there are many situations around the world that are not exactly peaceful, even if they are not in an outright state of war. Many people in developing countries, for example, cannot live in good health due to hunger and poverty. Researchers in developing countries pointed out that this too is a deprivation of peace, and this “North–South Divide”(*1) is now discussed as a peace issue.

Hunger and poverty are also serious problems in so-called developed countries. When such problems are not evident, that in itself is a problem. We must consider ways in which society deprives people of peace, and how this is connected to the world economy. Peace studies therefore began to reconsider its goals, considering anything that hinders the innate potential of human beings as “violence,” and mitigating such factors to the extent possible. This is a shift in perspective, one that considers not only direct violence but also “structural” violence. Wars between nations are also problematic, from the perspective that they oppress and harm human beings as individuals and destroy communities.

People have the ability to harm each other. Even the weakest human can kill another, given the opportunity. The same is true of family members. But peace research asks whether we can reach a point where, when disputes arise, we can resolve them without resorting to violence. At the very least, there is significance in working toward reducing such violence.

We cannot eliminate conflicting interests and ideals, our world being a creation of varied human beings, so trying to eliminate conflict can itself be considered as oppression. Such recognition that conflict is an inevitable part of human society is our starting point.

This is why people have developed various systems for nonviolently resolving conflicts between individuals, groups, and nations. Today we have banned methods such as duels or vendetta, and the eras of cowboy shootouts and gangster wars are relics of the past. The development of international organizations since the previous century has also made wars between nations illegal. We’re still working on that, but such efforts have brought us to where we are.

Even considering conflict as inevitable, we still witness wars that could have been avoided, accidents that very well have been prevented, and violence that ought to have been suppressed. It should be possible for we humans to reduce unnecessary tragedy, and that goal is worth the effort.

In peace research, we ask whether we can consider “conflict” as opportunities for better understanding ourselves and others. The idea is that perhaps we can defuse conflict situations, adding some slightly different element that reveals a more desirable path for each party. If you think about it, much of what we consider valuable are not those things we can take from others, but rather things we obtain by positively coexisting with them, love and friendship being good examples.

Such nonviolent transformation of conflict is the approach taken in peace research today. Rather than “solving” the problem of those in our way by killing them, nor making compromises to simply coexist, we seek an alternative path to find new collective values. Peace research is said to be future-oriented and value-oriented, in that it unflinchingly pursues how we can together create better futures for each other. That is the attitude we promote regarding all conflicts, from fights between couples to territorial disputes between nation states. This idea is not a panacea, but nonetheless it is an approach that is all too lacking in the real world.

What peace studies and peace research can accomplish in the face of nuclear threat

The explosion at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011 reminded us of the horror of nuclear weapons and the irreparable harm they can cause. Despite thirty years having passed since the end of the Cold War, there remains no prospect of dismantling all nuclear weapons. On the contrary, the proliferation of nuclear weapons has progressed since then, and many experts now believe that risk of their use is in fact higher than ever.

While the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons finally came into effect, it is being ignored by many nations, including the five nuclear-weapon states (the US, Russia, the UK, France, and China), others possessing or assumed to possess nuclear weapons (India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel), and those choosing to live under the “nuclear umbrella” of the United States, namely NATO countries, South Korea, and even Japan, which has itself been subject to nuclear attack. Today, there are over 13,000 nuclear weapons in the world. The accumulated destructive power is still comparable to stockpiles during the Cold War, a time characterized by phrases such as “balance of terror” and “overkill.” To our horror, increasing number of past incidents are being revealed where misperceptions, accidents or mechanical malfunctions have brought us to the brink of nuclear disaster.

Some people justify nuclear armament as necessary for “deterrence,” but that is a self-centered concept that does not consider countries who are the potential targets of nuclear attacks. Nuclear weapons are by their very nature offensive. If you do not intend to shoot a gun, it is wrong to keep your finger on the trigger while pointing it at someone (that is what nuclear deterrence is). The first step toward shaking hands is to lower your gun.

Imagine the risk we are under by having even a small number of countries, the United States included, with a finger hovering over the “nuclear button.” Imagine the horror that awaits if even one nuclear weapon is used, as seen in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Realism in the nuclear age paradoxically demands an idealistic response to eliminating both nuclear weapons and war.

Neither I nor my students know the reality of war. This makes it all the more necessary for us to know the facts regarding how wars continue to hurt people even after they end. Even if we only consider death due to weapons, disposal of unexploded ordnance is still a real problem in Okinawa and other parts of Japan. In northern France there are still injuries due to unexploded ordnance and land mines used in the First World War, more than 100 years ago. There is also damage caused by defoliants used in the Indochina Wars, the huge number of antipersonnel land mines and unexploded ordnance left behind there, and by depleted uranium ammunition in Iraq. Who knows how much “war waste” will be left for posterity in the ongoing civil wars in Syria and Yemen? Indeed, “war is the greatest form of environmental destruction.”

If you wish to train your imagination to address problems that are difficult to see in daily life, it is very meaningful to have the experience of not just learning from the literature, but by visiting sites and listening with your own ears to the experiences of those living there; it is important to engage in learning and study not just for the sake of obtaining knowledge, but to make that knowledge a part of yourself. Furthermore, the many wonderful people you will meet as a student will enrich your life. To that end, we are trying various forms of fieldwork in our curriculum, including off-campus training.

Every summer at the International Peace Research Institute, which I am currently the director of, students from Meiji Gakuin and American University in the United States study together and participate in the Peace Studies Summer Program (PSSP), through which they visit Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Tokyo. This is an invaluable opportunity for students from a country that has had a nuclear bomb dropped on it and students from the country that dropped that bomb to consider and converse regarding how we can overcome the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and our imminent nuclear peril. My current dream is to expand the PSSP into an international summer school program, through which we can learn peace alongside students not only from the United States but also from China, Korea, and other Asian countries. We need as many opportunities as possible for young people to interact and naturally expand their circle of friends.

What most saddens me in the COVID-19 pandemic is the news that increasing number of young people have decided to take their own lives. I would like to cry out to them, “You deserve to live!” I wish each and every one of you to embrace the life you are endowed with, and be proud of yourself. Peace means being able to do just that. Given that opportunity, I hope you will choose peace as your way of life, thinking about the “Others” in the school’s slogan “Do for Others.” Namely, let us be compassionate to the weak, and open our ears to the silent voices of the oppressed. That indeed is the cherished Meiji Gakuin spirit we hope to pass on.

(*1) North–South divide: This refers to problems arising from economic disparity between developed and developing countries and the resulting unfairness. This term came into use in the 1960s, when there were many developed countries in the northern hemisphere and many developing countries in the southern. Currently “global south” is more often used to address this unsolved problem.